|

From a Distance

Advocate warns against getting too close for creatures’ comfort

By SHERRY DEVLIN

|

|

|

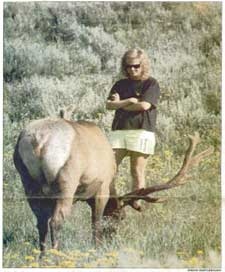

A bull elk is a spectacular sight, but looking this closely can be dangerous for both the animal and you, says Center for Wildlife Information director Chuck Bartlebaugh.

|

|

The message becomes mantra when Chuck Bartlebaugh brings his slide show of outdoor “do’s” and “don’ts” to grade-school classrooms and national park amphitheaters.

“Too close,” shout the children as Bartlebaugh advances to a slide of a young girl sniffing wildflowers, her back turned to a grazing bull elk. “Too close,” they shout at the photograph of tourists and tour buses, jammed around a roadside bear.

“The way to love wildlife is to respect it from a distance,” Bartlebaugh tells the children. They nod their uh-huhs. “What is wrong with this picture?” he double-checks, switching to a slide of a boy pursuing a mountain goat around a stub-topped pine.

“Too close.”

“And who is responsible for your safety?” he continues.

“Us,” comes the cry, little fingers pointing.

Bartlebaugh, through his Missoula-based Center for Wildlife Information, tries to counter what he estimates to be the $50 million America businesses spend each year on advertising that inadvertently gives people the wrong messages about wildlife.

Like the magazine ad several years ago that hoped to attract women to Dare perfume by showing a photograph of endangered species photographer Dianne Blell calmly snapping shots of a charging elephant. Or the plastic wrap commercial on television that features a black bear sniffing pies wrapped in competing brands.

“The advertising industry is telling people that it is OK to approach, touch and feed wild animals,” Bartlebaugh said. “It is not.”

The media also are at fault, he said. Bartlebaugh has a videotape of the “Today” segment in which Mutual of Omaha’s Jim Fowler fed a bowl of cereal to a bear, followed by a clip from the Discovery Channel program showing tourists feeding Cheez-Whiz to tropical fish off the Florida Keys.

Ultimately, the reach-out-and-touch-wildlife message manifests itself in bad behavior -- with occasionally disastrous consequences, Bartlebaugh said. His clip files provide proof.

There was the woman butted by a bighorn sheep, who later complained that she was just standing next to the animal as it grazed. When it had munched the grass closest her, the sheep knocked the woman out of the way and started on the grass where she had been.

Or the woman who skied along a bison grazing near Old Faithful and motioned to friends to take her picture. The animal gored the woman, then continued grazing. Or the man pulled from his RV by a black bear earlier seen foraging on human food at a nearby dump.

In each case, people died or were injured. Animals died.

Bartlebaugh’s own volunteers, who formed the Center for Wildlife Information in Polebridge 14 years ago, spent several summers quizzing tourists along roadsides in Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks.

“Eighty-six percent of them told us that animals on the road are tame,” he said. “A man from Toledo even went back to his car to show us the box of donuts he had brought to feed the grizzly bears.”

Thus, Bartlebaugh’s mission to educate the 42 million people who visit national parks and forests each year. He is convinced, he said, that people can and do change their behavior when they hear his words.

“It is our responsibility to give these animals room to live,” he said. “We all share the responsibility for our own safety and for that of the animals we observe or photograph.”

The National Park Service, Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Forest Service all support Bartlebaugh’s campaign Said Chris Servheen, grizzly bear recovery coordinator for the Fish and Wildlife Service, “If bears are to survive, even in the wilderness, they have to be oblivious to humans and human food. Wild bears don’t come into camp grounds at night. The bears in the campgrounds have a history of food rewards.”

“A fed bear,” said Servheen, “is a dead bear.”

Servheen said Bartlebaugh’s message is critical. “Anything we can do to impact public opinion will make a difference for the bears,” he said.

Bartlebaugh is particularly worried by the increase in injuries and fatalities among wildlife photographers in recent years. In every case, the photographer came too close to the animal, oftentimes a grizzly bear. And in most cases, the victim was alone.

There is no set distance that is “too close,” since individual animals differ in their responses to human encroachment. But there are warning signs: if an animal moves away from you, turns its back towards you, stopped eating, changes direction in travel, stands when it is resting or becomes aggressive.

Bears require extra precautions, he said. Even 1,000 feet of separation is no guarantee of safety.

“Bears can run as fast as horses,” Bartlebaugh said. “All bears can climb trees. Their eyesight is better than most people believe. A bear can interpret direct eye contact as a challenge or a threat.”

Wild animals in some national parks have become accustomed to humans and will let people come very close -- “too close,” Bartlebaugh reminds -- before reacting. They are not, however, tame.

|

|

|

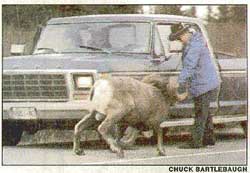

Hopping out of a vehicle to get a better look may be tempting, but just because an animal is near a road does not mean it is tame.

|

|

“It only means that when fight or flight is chosen, it may be too late for the human to retreat to a safe distance,” he said.

Buffalo look slow, but are very fast. They also have short tempers and will stomp or gore bystanders if they feel threatened. Moose will charge -- running, kicking and stomping -- when they feel threatened. And something as small as a dog’s bark can provide the provocation, Bartlebaugh said.

“Every year now, there is at least one death caused by a deer kicking, butting or goring a human,” he added. “Bighorn sheep and mountain goats also will butt people. This is a normal form of communication for them.”

The animals also suffer. Park officials often must kill bears habituated to human food, for fear they will attack visitors. Animals fleeing humans can abandon nests, run into traffic, lose their footing on cliffs or abandon an important food source.

“We’ve got to maintain a place for these animals,” said Servheen, “if we want to maintain the things that give us our identity and our sense of place. We’ve got to give them room to be wild animals.”

A View With Some Room

Teach child that they can protect wildlife by protecting themselves, Chuck Bartlebaugh tells parents. Wild animals pose special dangers:

- Children are the same size as some predators’ natural prey.

- Children should always be within immediate sight and reach.

- Children should be told not to play in or near dense brush.

- Children should not make animal-like sounds while hiking or playing.

- Children should be warned not to approach animals, especially baby animals.

- Children should never be encouraged to pet, feed or pose for photograph with animals in the wild, even if they appear tame.

“A fed bear is a dead bear,” says grizzly bear recovery coordinator Chris Servheen, who works with Bartlebaugh’s group to teach the dangers of feeding animals. To wit:

- Animals that are fed along roadways tend to frequent road sides, hoping for more handouts. The result: car-animal crashes.

- Animals that become accustomed to human food may eat aluminum foil, plastic and other wrappings. The result: severe damage to digestive systems, often causing death.

- Most animals’ digestive systems are not accustomed to human food. A poor, human-food diet results in tooth decay, ulcers, malformations, arthritis and other diseases.

- If garbage has an odor, animals may try to eat it. Do not leave boxes, wrappers or cans or any type where animals can find them. That includes film and cigarette packages.

Himself a nature photographer, Chuck Bartlebaugh has special words of warning for photographers, amateur and professional alike:

- All animals should be photographed from a vehicle observation area or from a distance with 400 mm or longer lens.

- Remain alert to potential dangers in your eagerness to take the perfect photo; 500 to 1,000 feet is recommended to avoid provoking large animals.

- Never surprise an animal. Retreat at any sign of stress or aggression.

- Avoid direct eye contact, even through the lens.

- Don’t crouch or take a stance that may appear aggressive to a wild animal. Avoid following or chasing, les the animal respond by charging you.

- Never try to herd an animal to a different location.

- Don’t make sounds to startle animals, especially animal-like sounds or wails.

- Never surround or crowd an animal.

- Avoid occupied dens and nests.

- Watch other people in the area. Are they putting you in danger?

- Stay out of dense brush

Reprinted with permission from The Missoulian and the author.

|